Annual Operating Planning (AOP): A Practical Approach for Product Leaders

It’s the time of year where leaders in all organizations are planning for next year, creating an Annual Operation Plan (AOP).

While these plans may not always unfold exactly as envisioned, they create a shared understanding among leaders and teams about key priorities for the coming year.

I recently facilitated a roundtable with several leaders about annual planning and distilled the discussion into an approach that is less painful and more fruitful.

Start with Financial and Strategic Goals

Use a Framework Like the W Framework to Structure Planning

Prevent Scope Creep

Align Different Groups with Roadmaps that Matter

Be Realistic about the Falsehood of Planning Precision

Evaluating Success: Retrospectives on Process Over Metrics

Start with Financial and Strategic Goals

Some Product leaders in our roundtable discussion were required to use company financial goals as the starting point of their plan. Some were not.

The consensus was that effective annual planning shouldn’t happen in a vacuum. It should be rooted in the company’s overall financial and strategic goals.

By aligning with these high-level objectives from the start, product teams avoid the disconnect that can lead to wasted resources and misaligned efforts. In many companies, employee bonuses are based on the company-wide plan so misalignment could have a monetary effect.

I did have a personal experience where a sales leader only projected revenue off of existing products. This made my return on investment calculations for new products very risky. Would a salesperson sell a new product if there was no quota for it? We ended up modifying the planning process to account for new products being launched in the upcoming year.

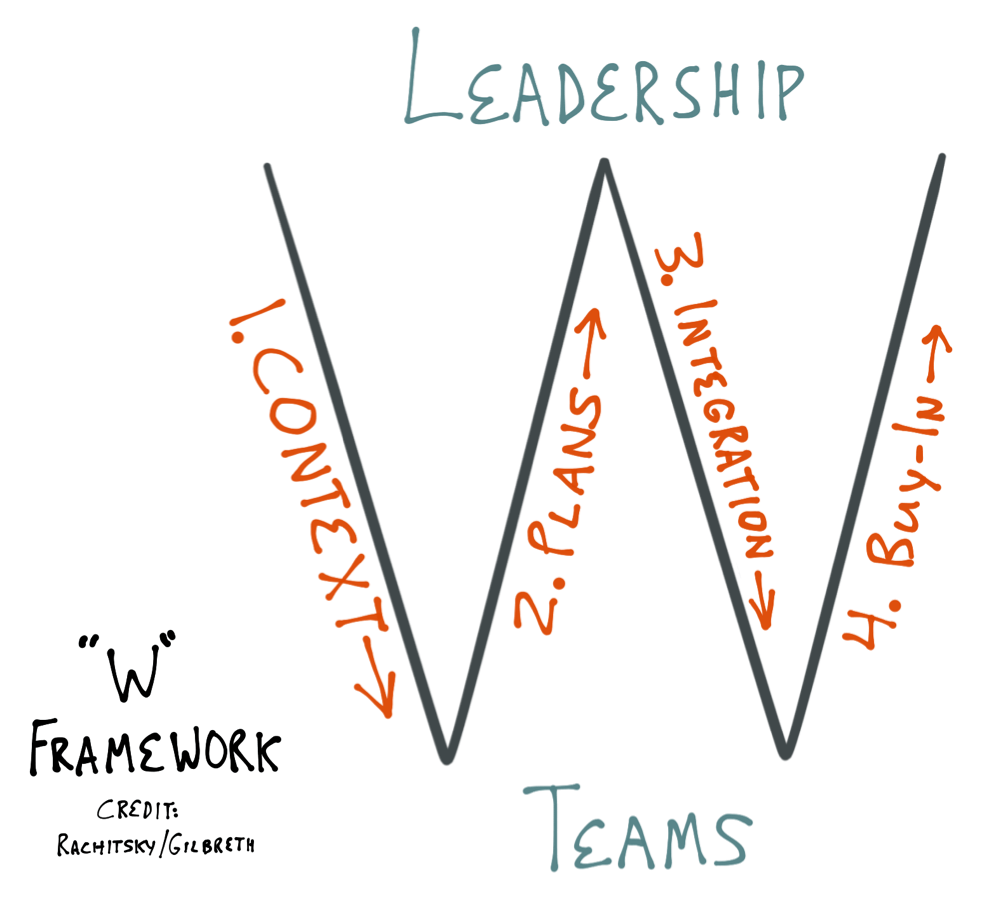

Use a Framework Like the W Framework to Structure Planning

Multiple leaders used the W framework as an easy-to-understand, collaborative approach to planning. The key components of the W framework include:

Context → Leaders provide high-level financial and strategic goals

Plans → Teams create plans aligned to these goals

Integration → Leaders unify into a consolidated plan

Buy-in → Teams and leaders negotiate a final plan

Writeup of the W framework (Lenny Rachitsky and Nels Gilbreth): https://review.firstround.com/the-secret-to-a-great-planning-process-lessons-from-airbnb-and-eventbrite/

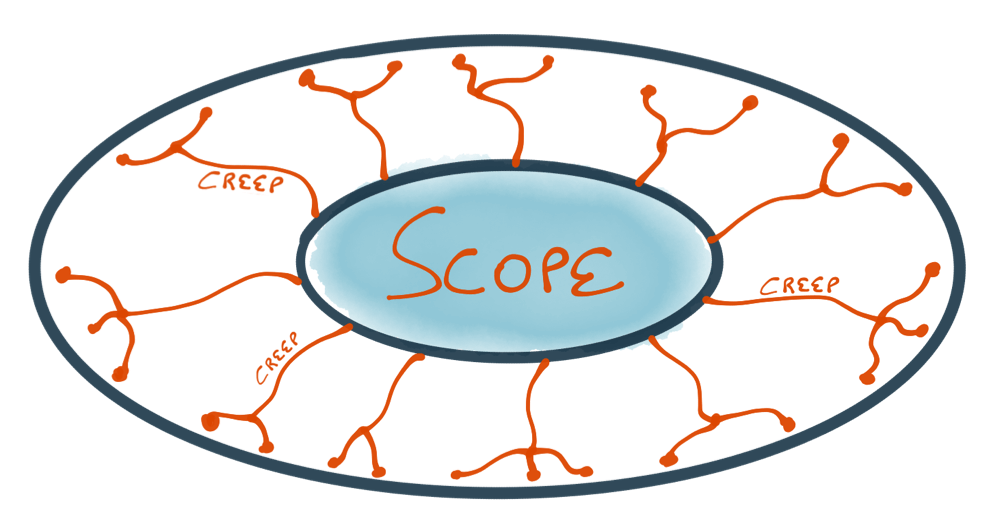

Prevent Scope Creep

Write down non-goals. These non-goals explicitly state areas the company will not focus on this year. Non-goals are a powerful tool to prevent scope creep by ruling out distractions or low-priority initiatives.

More on non-goals: https://review.firstround.com/set-non-goals-and-build-a-product-strategy-stack-lessons-for-product-leaders/

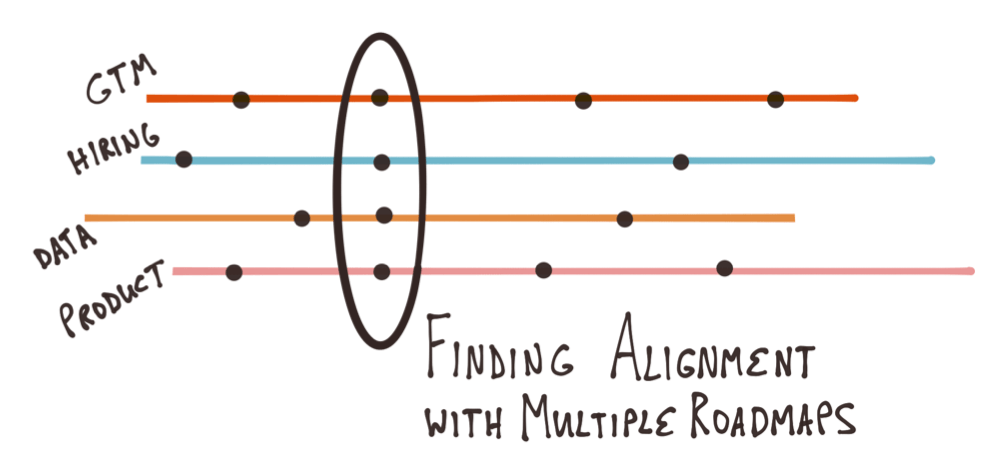

Align Different Groups with Roadmaps that Matter

Another valuable insight was creating roadmaps that showed key moments for teams that work closely with Product. By focusing on the most impactful roadmaps, teams can work in sync without becoming overwhelmed by excessive detail.

Consider these four roadmaps for effective alignment:

Go-to-Market (GTM) Roadmap - Coordinate with marketing and sales on upcoming product launches and key events, such as conferences or product summits.

Insights Roadmap - Line up the necessary data and research timelines to align to when important decisions will be made. These include customer research, data analysis, and competitor intelligence.

Product Roadmap - A simple Now, Next, Later roadmap can indicate to other groups what Product is prioritizing for critical features, improvements, and new offerings.

Talent (Hiring) Roadmap - Most AOPs include hiring. This roadmap indicates how fast new hires can be made and when they can start making an impact. Too often, organizations assume an unrealistically fast hiring and onboarding cadence and mis-estimate when initiatives can be achieved.

In a B2B SaaS company, it’s crucial for Product to be aware of important dates that the Marketing, Sales, Customer Success teams are focusing on. In consumer tech, there are behavioral rhythms triggered by holidays, changing of the seasons and more. These are different for every business and the Product team should take them into account.

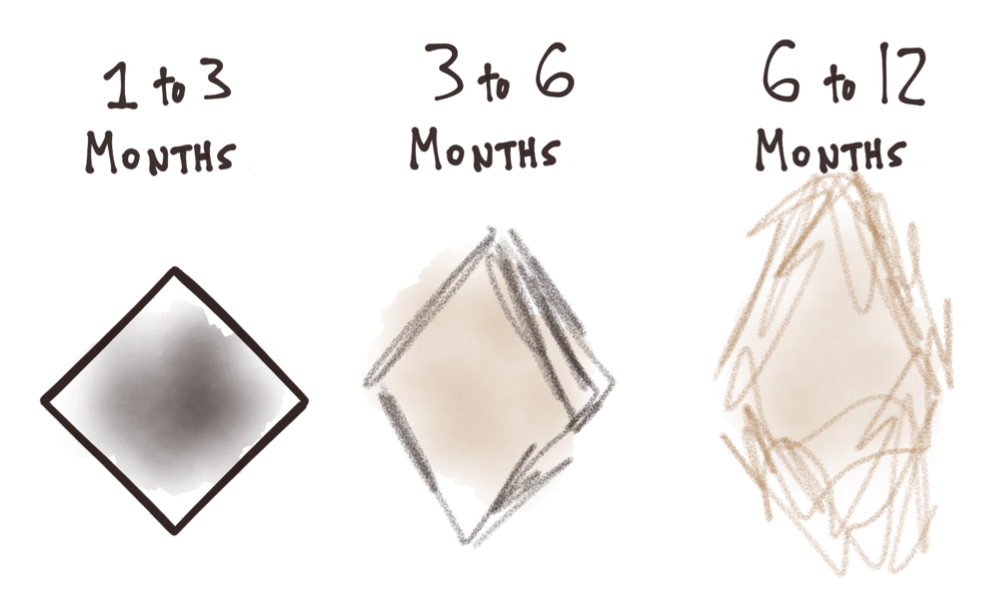

Be Realistic about the Falsehood of Planning Precision

Leaders in this roundtable found it challenging to strike a balance between precision and predicting the future.

Demanding detailed plans for rough ideas ignores the inherent uncertainties in business environments, especially in fast-paced industries like tech.

This can lead to wasted effort and resources, as these plans may need significant revisions or become obsolete.

While planning is essential for alignment and achieving goals, it should incorporate flexibility alongside precision.

The AOP process should strive for a middle ground between exact planning (the future is not that certain) and a free-for-all (autonomy is too risky).

One leader mentioned providing an estimate of 31.5 weeks for building a feature that had very little definition. These high precision, low information estimates seem to be commonplace in planning.

The issue with creating a year’s worth of these overly detailed estimates is that leaders often pivot priorities every 2 to 3 months. This isn’t a bad thing. It’s likely good for the business to respond to the market rather than push forward for the sake of sticking with the plan.

The takeaway is to spend less time making overly precise estimates for far-in-the-future concepts. As you plan further into the future, use time ranges instead of precise estimates or a range of possible solutions which reflect the fuzzier confidence that concepts will still be important 9 to 12 months from now.

It could be more effective to just move to “QOP”... Quarterly Operating Planning.

Evaluating Success: Retrospectives on Process Over Metrics

Conditions change, priorities shift, and sometimes the best outcome is one that deviates from the original vision. Most product leaders admitted to not comparing results to the original plan. Instead, they said it was more useful to focus on evaluating and improving the AOP process itself.

Use the philosophy of “look-back-to-look-forward” to conduct a retrospective to find valuable insights for improving next year’s AOP. For example, if you find that the slow speed of hiring slowed progress, this insight informs future talent roadmaps. Or, if the GTM roadmap fell short in syncing launch dates with marketing efforts, this feedback helps refine cross-functional coordination in the future.

The usual retrospective framework of “start, stop, continue” can apply here.

Conclusion

Annual Operating Planning seeks to predict the future. Tech companies are constantly evolving and operate on much faster timelines than traditional businesses. The planning process should reflect this uncertainty and use a lightweight approach such as the W framework. Precision should be reserved for a shorter time frame of a couple months.

AOPs can and should be aligned to overall company goals and to other organizations within the company. To improve year over year, Product leaders should lead retrospectives on the process for Annual Operating Planning.

The result? An Annual Operating Plan that empowers product teams to work strategically without getting bogged down by detail, while ensuring that every initiative contributes to the company’s overall mission.

Many thanks to the Product Leaders of Supra who made many of the process suggestions.

Jim coaches Product Management organizations in startups, growth stage companies and Fortune 100s.

He's a Silicon Valley founder with over two decades of experience including an IPO ($450 million) and a buyout ($168 million). These days, he coaches Product leaders and teams to find product-market fit and accelerate growth across a variety of industries and business models.

Jim graduated from Stanford University with a BS in Computer Science and currently lectures at University of California, Berkeley in Product Management.